… children who are presently disadvantaged.

If we are to overcome the forces in our society and schools that insidiously widen gaps, between those that have and those that have not, we need to be more ferocious, more tenacious in creating the conditions that enable our disadvantaged learners to flourish. This requires educators to be more honest, to ask uncomfortable questions and make braver decisions to fiercely educate those that need us the most.

To fiercely educate is to replicate the stage-managed, high expectation and sharpened elbows of an advantaged childhood. Being fierce means guarding a child’s education, expecting much, staying alongside, pushing from behind, consistently and persistently championing individual children.

An advantaged childhood holds, expects and elevates children, who are fiercely loved and as a result feel more secure.

“Okay, well, Eleanor has this mother. She intimidated me at first actually because she just – she’s fierce. Fiercely loving. … but I could tell she felt safe in that house. She grew up feeling safe and fiercely loved.”

“And you and I didn’t get that, not because we didn’t deserve it, we just got dealt something else. But the people who did get that love, they grew up to be different from us. More secure.”

Coco Mellors | Cleopatra and Frankenstein

To be fiercely loved* is to be challenged, extended, stretched, to reach and risk, and at the same time, to be held tightly, more secure. “You will be brave, I have got you.”

*the emphasis is on fiercely rather than loved. Families who are socio-economically deprived do not love their children less, often quite the opposite, but the time, money, space to create opportunity and supported experiences to translate that love, ferociously, is compromised at every turn.

Advantaged families interpret the world for their children, translating experiences and interactions to maintain their sense of security and renew their agency. Setting and re-setting a desired narrative of what it is to be and feel successful, to step forward once more, even when the randomness of life and experiences intrude beyond the home. There is always an ongoing invitation to dance. Sitting out is not an option.

To grow up advantaged is to step forward through a life punctuated by opportunities, reaching, risking and stepping forward, it is a secure pursuit. These are childhoods, with guide ropes and safety harnesses, that see failure as an obstacle on the path to eventual success.

“If you are lucky enough to be born in a world made in your image, you probably think of a failure as an obstacle on the path to eventual success. If you are a marginalised person in any way you internalise that failure more closely.”

Elizabeth Day

Without a deep sense of security, a disadvantaged child is far more likely to internalise failure more closely. It is precisely this self-reflection, the connection of failure with self that perpetuates over time and maintains an inhibiting mindset that convinces that it would be safer not to try. Without the ferocity of expectation, the unwavering (taught) belief in their own agency, a child’s hand goes up fewer times, they step back rather than stride forward and live with a constraining belief that the world is not built in their image or for their circumstance.

If we step forward less we tend to surround ourselves with others who are also less likely to step forward in life. It is the five closest individuals with whom you measure your status, the ones that set the bar, the ones we compare against. And where we create schools within schools we set expectations of what is possible (and not possible). We must work harder to cross-connect social circles, orchestrating and intervening to be more inclusive.

“Each starling is only ever aware of five other birds,” she said. “One above, one below, one in front and either side, like a star. They move with those five, and that’s how they stay in formation.”

“Who are your five then?” asked Cleo. “The ones you watch?”

Coco Mellors

It is an inconvenient truth that schools create these self-fulfilling groups, reinforce the conditions for advantage and disadvantage to accumulate. We are the problem more often than we admit, more often than we see, more often than we realise. To see the conditions we create, those that we have come to accept, we must apply the disadvantage lens on ourselves and our schools, be more honest and evaluate what we are willing to accept, what we hold up and measure as success. This is about confronting and tackling the perpetuating inequity, seeking to halt social fractures at a time when society is fracturing.

Hope: to want something to happen or to be true, and usually have a good reason to think that it might.

A childhood of advantage is one of agency and hope; a life on an exciting journey of opportunity, where what is wanted, sought after, is within reach and based on previous experiences, have a good reason to think it might be achieved. And if it does not, any failure slides off, it does not define. After all, the failure is not about me reaching out, because I act on the world. And yet for our disadvantaged children each failure is another hit on self-belief, self-image, another example of the world acting on them. “This world is not for me.”

An advantaged childhood also has purpose (one insisted on, and then internalised by the child), a beacon that directs effort and demands persistence. We must work harder to create, expect and articulate purpose so that it fuels the persistence required to close gaps.

“When we have a purpose, we are able not only to endure and persist but also to provide a beacon that reminds us of what’s important and to make the right decision at the right moment.”

Steve Magnus

Too many journeys through school are riddled with children being let off, in conditions of low expectation where interactions are compromised by collusion. We are prone to making poor assumptions about background, present levels of attainment, context, aspiration, resilience; missing the fact that we are both the problem and the solution.

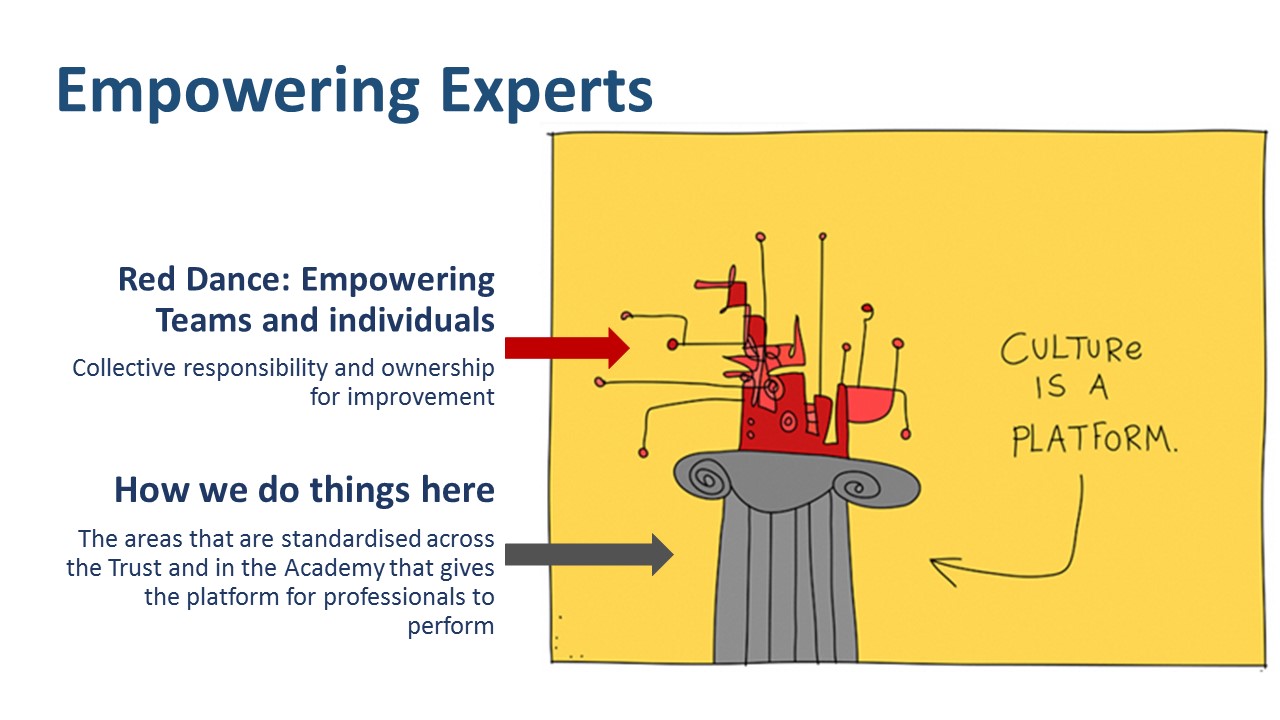

We need to be more honest and braver as educationalists, guarding each child’s education and building great schools that deliberately step in to create pathways for disadvantaged learners to thrive and flourish. It takes the whole team to maintain provision that privileges disadvantage everywhere, only shared endeavour has any chance of systematically closing gaps; culture over lists of good intentions/interventions.

So:

- There is little in this world more powerful than someone who deeply believes in you; educators have that power. An unconditional acceptance from a trusted adult gives a child the warm sense of belonging; a psychological safety that says we believe in you. Unpicking disadvantage is a team sport, focused on individuals to apply equity.

- We are disproportionately influenced by those that we spend time with (sometimes chosen, sometimes destined, sometimes orchestrated); schools need to remove the school within school phenomenon – our choices around setting, staffing, curriculum either perpetuates disadvantage or removes it.

- To fiercely educate is to have educational provision that reaches those that need us most. We need to measure what matters: the attendance and attainment of disadvantaged learners. Attendance first… we cannot fiercely educate any child we cannot see.

- Our journey through education is disproportionately shaped by small acts; these are rare, often serendipitous experiences that shape us the most. How far do we purposefully engineer and create these moments of ignition within a child’s education so that they see themselves differently?

The disproportionate influence of five sentences within the novel of our lives.

- Our interactions, language and the attention we give to others defines our attitude towards them and influences the way children see themselves. It is easy to understate the importance of culture and collective attitude in schools.

- A child’s self-belief, self-confidence and self-image can be so fragile that inconsequential comments, experiences and actions can erode any belief that exists. As educators we can choose to fill or not fill these lockers. Removing deficit and neutral discourse in our shared language really matters; our words make a difference, both ways.

- Simply adding “I am giving you this feedback because I believe in you,” changed students’ learning trajectories significantly (Cohen & Garcia, 2014).

“They may forget what you said, but they will never forget how you made them feel.”

Carl Buehner

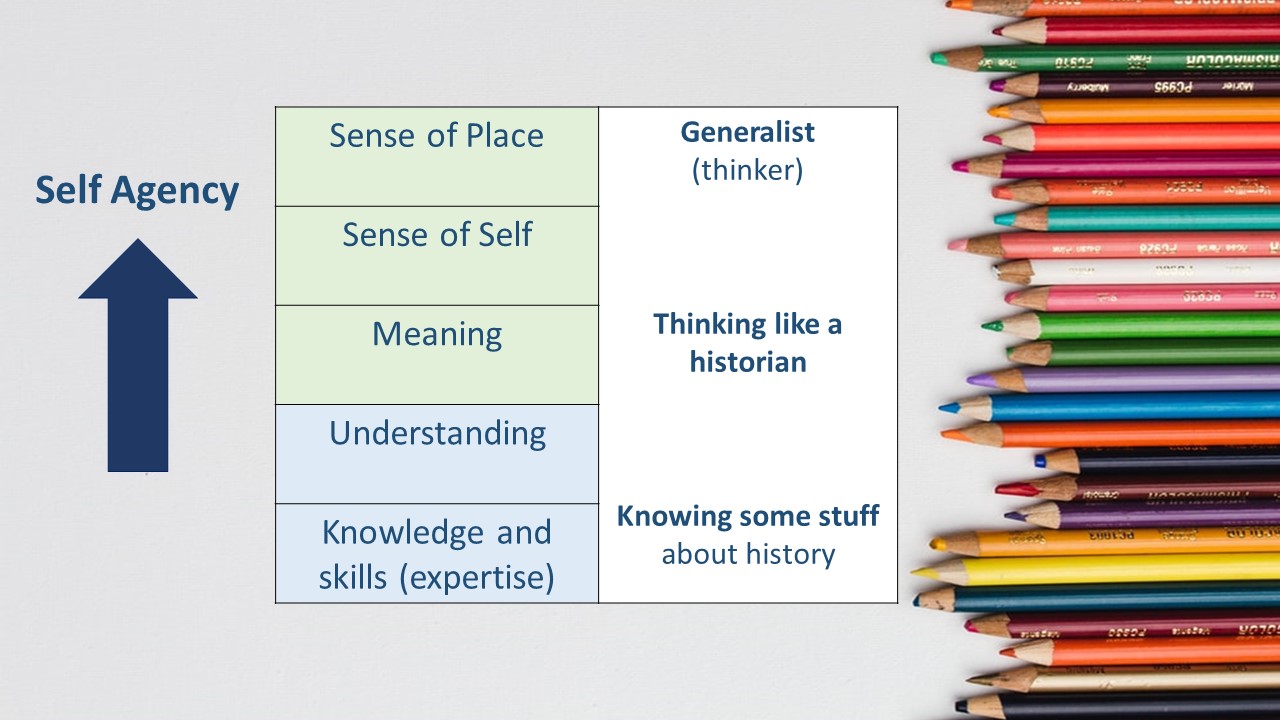

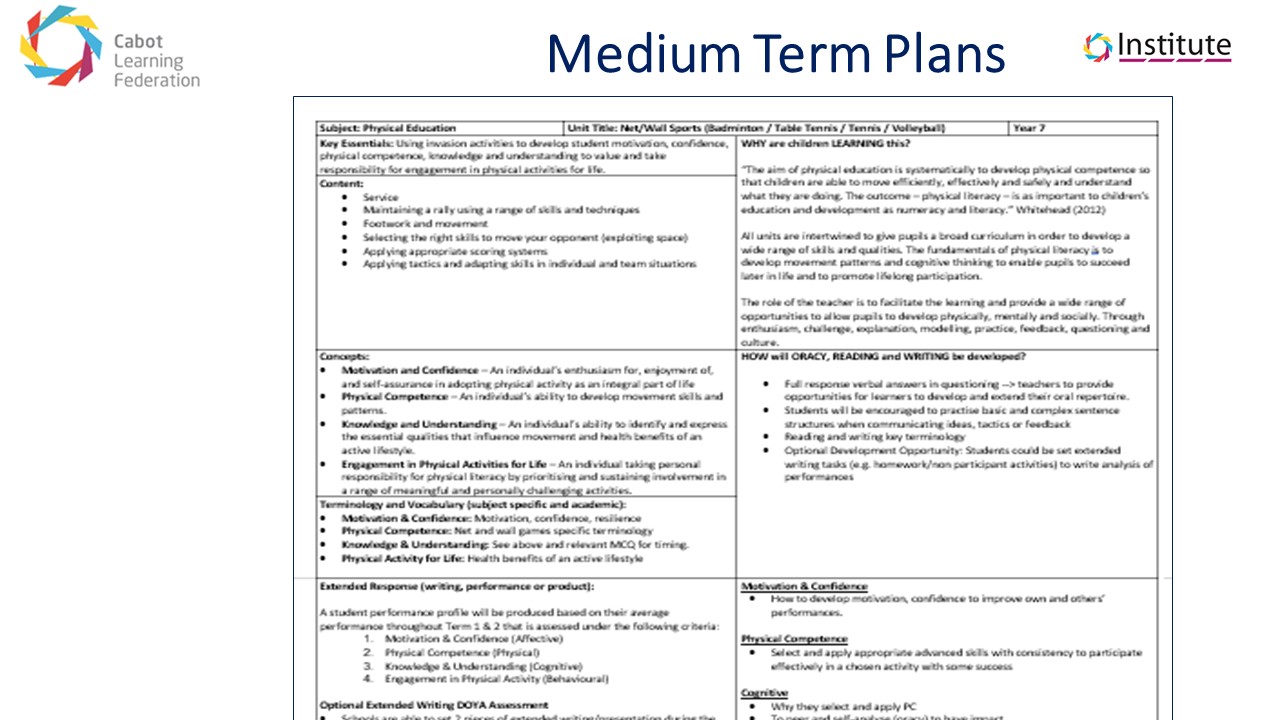

- We need great teaching in great schools to understand where children are in their learning and teach the next bit. Seeking to hunt not fish and to apply the equity that disadvantaged learners need. Weaving nets to catch the curriculum.

- We are hard-wired to see success as talent and gift and not the expression of supported opportunity and accumulated hard work over time; it is the latter that disadvantage learners need, it is the former that perpetuate poor attitudes to individual potential and widens gaps.

- We may well be witnessing a significant shift in the social contract. The contract held between families and school is eroding, relationships and attitudes are shifting. Whilst we wrestle with a whole range of challenges we must not forget, rather increase our investment in the individual children that walk into our schools everyday.

- … you have the power to change lives, to weave a future for children, just as the threads of society are unravelling for too many children. You are the hope, for many the only second chance.

“History will judge us by the difference we make in the everyday lives of children.”

Nelson Mandela

Dan Nicholls | May 2023